Oh, to be back in Tucson!

I ended my last post on a high note, congratulating myself on a solid stretch of solar-powered mobile freedom. My experience in Arizona was so joyful that I could imagine other people wanting to do what I was doing, which was a new feeling for this trip. I caught myself daydreaming a future of solar boondocking with friends — a whole climate crew sipping on sunshine, hiking and zipping around on e-bikes together, cooking communal meals with our mobile kitchens. (If this sounds like your idea of a good time, you know how to reach me.)

Well, times have changed. For the past few days I’ve been in oil-and-gas territory in West Texas, and it appears that my era of energy independence is over. This phase of the trip has involved a series of mishaps, concessions, and compromises that, while certainly not the end of the world, have left me feeling a little defeated.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Monday

Back in Tucson, the morning after my last post went up, I had to catch an 8:45 am train. I set an alarm for 6 am, thinking that would give me an hour to pack up camp, another hour to bike the 16 miles from the horse ranch to the station, and still leave plenty of time on the platform for transformation into train mode: packing the contents of my panniers into a big duffel, folding up the e-bike, charming the Amtrak employees into waiving the baggage fee, etc.

When I awoke, it was far brighter than I was expecting for 6 am. The sun was clearly about to poke above the horizon, and my watch informed me that it was in fact 7 am. Apparently, I had somehow botched the whole alarm business. I had to laugh. It was as if old Jake (absentminded, logistically-challenged) saw the emerging Jake (competent, careful planner) patting himself on the back, and reared up to say: “Not so fast, buddy.”

I laughed, and then I busted my ass for 90 minutes to catch that train. I packed up camp in 30 minutes flat, put the bike in Turbo (the highest level of e-assist), and shouted a final thanks/goodbye to Lou as I peeled out of his gravel driveway. Google maps estimated that biking to the station would take an hour and fifteen minutes, putting my arrival at 8:45 am: probably not good enough to catch the train. But Google maps didn’t know about the 400 watt-hours of sunshine I had at my disposal. I was pretty sure I could make the trip in under an hour.

I pedaled as hard as I could, never more thankful to be on the pedestrian-only Tucson Loop. I would have had zero chance if had been contending with cars and stoplights, but with the bike path to myself, I was able to keep my speed around 20 mph nearly the entire way. I grew simultaneously incredibly cold and incredibly hot: the air whipping past me was barely above 32 °F, and my hands, feet, nose, and ears were underdressed and soon grew numb. My arms, legs, and core, on the other hand, were far overdressed and pouring sweat. But I didn’t think I could afford to stop and adjust. I just kept pedaling and eyeing the estimated arrival time, which was steadily ticking downward.

As I rolled into Tucson at about 8:20, I could hear the train’s whistle coming up behind me. It was comical; the train was clearly going to beat me to the station, but by how much? I pushed through the final leg, now on city streets, and barged onto the platform, where I was accosted by an Amtrak employee.

“Are you trying to catch this train?” he asked.

“Yes, am I here in time?” I huffed, out of breath.

“Yeah, but you have to wait like everyone else. Boarding line starts over there.”

Shoot — got off on the wrong foot with that employee. But I had made it.

Thrilling, skin-of-your-teeth experiences like that are what sustains a poor planner’s bad habits, and I rode that high for the entirety of the 12-hour train trip to Alpine, Texas. I was in such a good mood that I didn’t even mind the hour I had to spend in the train lavatory, washing the Dr. Bronner’s off of everything in my backpack. (In my rush to pack up camp, I hadn’t put the bottle of soap in a Ziploc bag. The Dr. Bronner’s always has to go in a bag.)

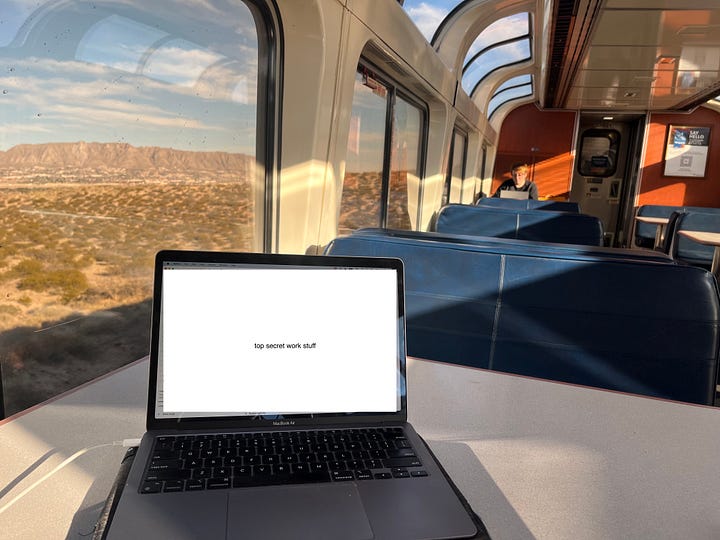

Working on my laptop in the train’s sightseer lounge was delightful — there is something about the endless motion outside the window that I find very conducive to deep thought. Our route passed through El Paso, across the border from Ciudad Juarez in Mexico. El Paso was a long stop, with time for passengers to get off, walk around, smoke a cigarette, or — in my case — pay a visit to the burrito lady, who apparently has been meeting the Sunset Limited train three days a week for over 20 years. Her burritos were, unsurprisingly, super legit. Shortly after leaving El Paso, we were treated to an epic, whole-sky-on-fire sunset.

As we neared my destination of Alpine, TX, it became clear that the train was running over an hour late. My plan, which was starting to seem not-so-good, was to bike 26 miles from Alpine to a campground in Marfa, TX. This would be my longest bike segment yet, and my legs were still smarting from the surprise sprint to Tucson earlier that day. Due to the late arrival, I would be starting at about 10 pm, and as I looked out the train window, it appeared that Alpine, TX was living up to its name: mountainous, elevation 4,500 ft, often quite cold in the winter. With a growing sense of doom, I realized that my bike route to Marfa would be primarily along a two-lane highway with a speed limit of (checks Wikipedia) 75 mph.

There’s no sugarcoating it: I had made a bad plan. Just because Google maps will plot a bike route for you doesn’t mean anyone in their right mind would actually ride that route. (App idea: bike route planner with safety bumpers for those without a death wish.) I was waiting by the train door with all my stuff, steeling myself for what would surely be a tough ride, when I saw that my seat mate was getting off the train too. We hadn’t spoken much on the train, but now I made fun of him for wearing shorts, probably to make myself feel better about how unprepared I was. He asked if I was backpacking, and I clarified that I was bikepacking, as if that made it better. But it turned out that he was headed to Marfa, too — and getting picked up by a friend with a car. Before I knew what had happened, I had blurted out: Might this friend have room for an additional passenger, a folding bike, and a bunch of solar gear? A quick text exchange ensued. His friend thought it was worth a shot.

As we stood there chatting, I learned that my seatmate, whose name is Pat, lives in Provincetown, Massachusetts. He had flown into El Paso, where he caught the train, and was headed to Marfa for a poetry workshop run by the very friend who soon pulled up in a Prius and honked. This friend, I learned, is both very generous and very well-known (they have an excellent poem in the current issue of Harper’s). It was tight, but my bike and everything else fit in the Prius, and as we drove the two-lane highway to Marfa in the dark, with semi-trucks roaring past in the other direction at 80+ mph, I knew I had made the right decision. I like to challenge myself, but there’s a big difference between hard and downright dangerous.

The poets delivered me safely to Marfa, and I set up camp in the dark, a little starstruck under the big open sky.

Tuesday

The next morning was cold and overcast. I had full batteries, so I made some oatmeal for breakfast inside my tent and biked to town to get a few groceries. I set up my solar panel and pointed it where I thought the sun was — it was nearly impossible to tell, with all the cloud cover — and pulled a measly 10 watts. I love clouds, but they are not your friend when you’re solar-powered; there was no chance I could refill my battery enough to cook dinner. Bummer.

Seeking warmth, I spent most of the day working on my laptop at a coffee shop in town that adjoins a laundromat, where I gave my two outfits a long-overdue wash. Marfa felt like a ghost town, probably because it’s not tourist season and fewer than 2000 people live there anyway. Plus, the weather was awfully dreary. The forecast called for the overcast to turn to an all-day chilly rain for Wednesday.

I biked back to my tent shortly before dark to make sure that my rain fly was staked properly to keep things dry during the coming storm. While I was inspecting a line, my bike fell over behind me. “That’s weird,” I thought — it had never lost balance like that before. Then I realized it had fallen because my rear tire had gone completely flat.

The prospect of fixing a flat tire in the coming cold rainstorm got me thinking that it was time for another compromise. I was camping at El Cosmico, which the local Marfans accurately refer to as a hipster trap. In addition to decently affordable tent camping, which includes access to communal outdoor baños, El Cosmico also offers several more substantial but overpriced lodging options, including trailers, teepees, and yurts. I walked around the site, weighing my options, and came upon a handsome yurt with a green door. It looked cozy. Then, around back, I saw that this yurt had a heat pump. That sealed the deal — if anything gets me as excited as a bunch of solar panels, it’s a heat pump. I upgraded at the front desk and moved into my yurt for the storm.

Boy was it luxurious in there. After days of careful energy rationing, suddenly I had unlimited electricity. The heat pump, pulling up to several thousand watts from the grid, could easily keep the yurt at a comfortable 70 degrees — or significantly warmer, if I wanted a sauna experience. I could simultaneously run the heat pump, my induction stove at its maximum power of 1300 watts, a space heater, and a fan, all while charging my e-bike, laptop, and cell phone. Famine to feast!

Once I was unpacked and comfortable, I thought about fixing my flat, but I had already decided that I wasn’t going to try to bike back to Alpine to catch my next train. The rain storm we were getting was going to be an ice storm in Alpine and other parts of Texas, and that highway wasn’t going to get any safer. So, while I needed to fix my flat, I also needed to find a ride back to Alpine. I decided to prioritize finding the ride. I headed into town, ready to flirt like my life depended on it.

But the only person at the Hotel St. George bar was Pat, the poet from P-Town. He couldn’t be my ride — he’d be busy with the poetry workshop on Thursday, the day of my train — but that was OK, because he was quickly becoming my Marfriend. I gave up on my ride search for the night, and Pat and I hung out at the bar. I ate dinner while he drank decaf.

Wednesday

The next day, I spent the morning in the yurt fixing my flat tire. The storm had arrived as promised, and the rain was making a ruckus on my roof. Nothing makes you appreciate shelter like a storm.

Getting the rear wheel off was quite difficult without a bike stand, but I managed. Inspecting, I discovered that my tube had been punctured by a burr from a plant that is literally called “puncturevine” (or Goat’s Head, or Devil’s Eyelash). I wasn’t too surprised: these little burrs were everywhere. I stepped on several dozen, painfully, throughout my stay at El Cosmico — if my feet were inflatable, I would have been caught flat-footed more often than not. The puncture was so small that I lost it immediately after removing the burr, and I had to submerge the tube in the communal baño to find the leak.

Applying the patch was straightforward, but both bike pumps at El Cosmico leaked enough that they couldn’t fully inflate my tire. I suited up in my rain gear, rode the bike with a barely-inflated rear tire to the nearest gas station, paid two dollars, and filled ‘er up. The patch held! I rode back to camp smiling. It was a satisfying repair — enjoyable, even — and the adventure into the cold rain for air was completely tolerable because I knew I could go right back to my cozy shelter.

Back in the yurt, I made a call to the Marfa Visitor Center and learned that they have a group of retirees on speed dial who offer rides to and from Marfa. I arranged for Belinda to pick me up on Thursday evening and take me back to the train. That was both transportation problems solved — how’s that for some logistical prowess!

I met up with Pat later that afternoon, and he snuck me into the Hotel St. George gym for a workout.

Thursday

I’m writing this post on the train to New Orleans. I’m back in the sightseer lounge, although it’s pitch black out. My ride to Alpine with Belinda earlier today was smooth — plenty of room for everything in her Toyota 4runner. Belinda and I hit it off right away over a shared love of Big Bend National Park; she had spent the previous weekend there photographing and measuring the sizes of bluebonnets, as she often does. The train was only 10 minutes late, and I’m finally getting the hang of the boarding routine.

Looking back, it’s clear that if Tucson was my independent era, the theme of my time in Marfa is: Dependence. Dependence on fossil fuels, for safety and comfort; dependence on the generosity and friendship of strangers, to get around and to keep my spirits high.

It’s an instructive reminder. We’re all in this together; independence is an illusion in all but the most extreme cases. We’re not going to stop global warming by convincing everyone to become solar-powered e-bike nomads; we all want to keep taking hot showers, driving comfortable air-conditioned vehicles, living with an abundance of energy always on tap. That’s why I (and many others) believe the way to stop global warming is by electrifying everything — all the activities and services we need to live safe, comfortable lives — and supplying that electricity with a grid that is overwhelmingly powered by wind and solar.

My all-electric yurt experience was halfway there. Although I wasn’t burning any lumps of coal or burning natural gas myself, there was a lot of fossil fuel combustion behind all that grid electricity I was happily guzzling. The Texas electricity grid’s “fuel mix” is about 60% fossil fuels (40% natural gas, 20% coal), the rest made up by wind (25%), nuclear (10%), and solar (5%).

This is not particular to Texas: no matter where you live in the United States, the grid is propped up by fossil fuels, and most of us still operate fossil-fuel-powered equipment every day. This means that we’re a long way — likely many decades — from stopping global warming. It will be a long battle, and that makes it all the more important to keep the goal clearly in sight: electrify everything, and clean up the grid. The hard part is figuring out how to get it done as safely, equitably, and quickly as possible.

— Jake

That yurt is the bee's knees! It's very lucky you got rides to and from Marfa, but too bad there are not better biking alternatives.

Yes, electrify everything! Jake, I’m sure you already know about this but other readers might not. I’m so delighted for the work of Mark Jacobson at Stanford. His arguments are so compelling: https://a.co/h5MWqWq