Running from clouds

A total e-clipse of the heart

I had heard that people cry during solar eclipses, and I get it now.

Most eclipse weepers probably turn on the waterworks during the “totality” phase, that awe-inspiring stretch of time when the sun is briefly replaced by a psychedelic black hole. But not me. My emotions are right at the surface these days, and I sprung a leak before the partial phase of the eclipse had even begun.

My night of stealth-camping in the truck was mostly comfortable, although I did wake up pretty cold at about 3 am. I turned on the truck’s heater for a while to take the edge off my chill. This cost me a few kilowatt-hours, or about 10 miles of range — well worth it to stop the shivering and allow myself to drift back to sleep.

Once the sun was up, I rolled the truck back over to the library and reclaimed my parking spot. Almost immediately, other cars started to pull in. Parking lots started filling up by 9 am. A free popcorn stand had appeared, and was doing steady business. The town was alive!

I had seen a sign advertising a “solar eclipse brunch”, so I headed over just early enough to grab a table before there was a big line out the door. The atmosphere in the café was electric. Of course the eclipse was all anyone was talking about. The man at the table next to me asked the server if he ought to head up to Quebec, to get a slightly longer dose of totality, or if he should venture further east to avoid any clouds that might be coming in from the west. The server didn’t even hesitate: “I think right here at Island Pond is just about the best spot you could find.” I had to agree. For now, at least, the sunny conditions we all hoped for had arrived. Warmth was streaming in the windows. My brunch came with eggs, and you can guess how I ordered them.

After breakfast, I headed back to the sandy lake beach, where folks were staking out tents and setting up picnic blankets. People had clearly traveled far, some having driven through the night due to the shifting cloud forecast. I set up my camping chair and watched the sun ascend ever higher over the frozen lake. The day was getting warmer by the minute, and the view was spectacular.

And that’s when I started to get emotional. The more I contemplated the symbolism of the day, the more I began to see it as a culmination of my personal evolution over the past few years.

During my time as a climate science researcher — roughly the past decade of my life — I have had a particular focus on clouds. This began back when I was 21 years old, soon after I decided that I wanted to apply my physics background to the climate problem. On a hike in the beautiful hills above Berkeley’s campus, an ex-string theorist (who went on to become my PhD advisor) convinced me that clouds were the biggest unsolved problem in climate science. Looking back, I can imagine what I must have been thinking to myself. “You’re telling me that clouds — these beautiful, shapeshifting ghosts in the sky, which I have marveled at since I was a kid in the cornfields of Illinois, are full of physics mysteries? And they are directly relevant to global warming?”

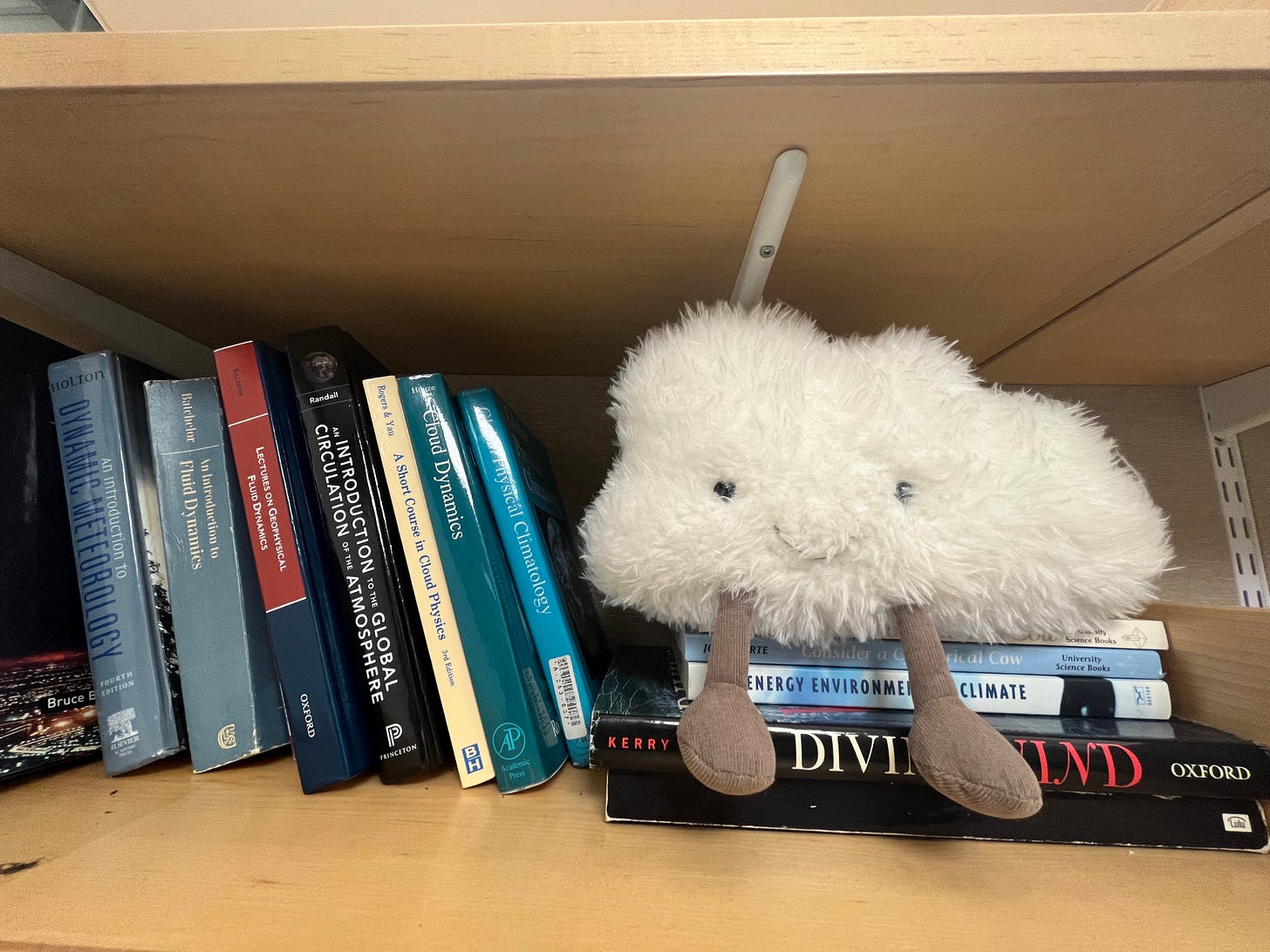

OK, my internal monologue probably wasn’t that eloquent. But I was sold. And once I started grad school, it didn’t take me long to really fall in love with clouds. I thought about them like it was my job, because it was my job. I went to conferences and gave talks about what I had learned about clouds. I got into academic brawls (settled in the literature, of course) about why certain types of clouds form where they do. It’s fair to say that during this phase of my life, I came to identify with clouds. My Instagram account is mostly pictures of clouds (with a few bugs mixed in for variety). Friends often send me pictures of the sky, asking me to explain some strange cloud formation. In my office, a cute stuffed cloud is perched on the shelf next to all my textbooks.

As my dad once wrote to me, life is good when you’re doing something you love. For many years, being a climate researcher felt like the best job in the world. But I don’t want to have my head in the clouds anymore. I’ve had enough of writing papers about clouds and the physical climate system.

How did it come to this? I started to suspect something was wrong about three years ago, when I went “on tour” to talk about a paper that I had recently published with my postdoc advisor. The paper was in a high-profile journal, and the publicity tour should have been a celebratory moment. But on my campus visits I was having out-of-body experiences. While giving my talks I felt like I was pretending to be excited about my work, and I hate pretending.

I knew I needed a change of pace, so the summer after that dissociative publicity tour, I took a “sabbatical” from research to work on an organic vegetable farm in Vermont. I will always be grateful to my postdoc advisor for supporting me in this decision, which proved to be pivotal. Within a few weeks of starting to work on the farm, I realized that I felt happier, healthier, and less anxious than I had in a very long time. I loved being part of a team with the common goal of growing delicious food. I loved being valued for my strength and stamina. I loved working outside, how attuned I was to the rhythms of the seasons and the weather. I loved the way deep, intimate conversations seemed to just flow as the crew weeded a field of carrots or harvested beets. I made lifelong friends. Only half joking, I started to refer to the academic track I had temporarily stepped off as the “smartypants contest.” (To my many friends in academia, please forgive me for this phrase — I’m not talking about you!) It was just a few months, but that summer on the farm was when I started to deliberately turn away from clouds.

And at the same time, I began to turn towards the sun. While working on the farm, I lived in a little cabin that didn’t have running water or electricity. So, after a few weeks of reading by candlelight, I rigged up a simple solar electricity system. This was very satisfying, and I noted a distinct spark of curiosity. I began to daydream about working on the climate problem in a way that was more hands-on, more boots-on-the-ground. There’s more to solving climate change than putting up solar panels, of course, but the clean energy we can harvest from the sun is going to get us most of the way there. Plus, clouds weren’t really doing it for me anymore, and the sun is, like, totally the opposite of clouds.

These thoughts were floating around in my head when I cautiously returned to the smartypants contest in the fall. I was worried that my mental health would take a nosedive when I returned to Boston, and it did. I pushed through another semester, got another paper out, but it was a struggle. Then, in an attempt to recapture some of the excitement and well-being I had felt on the farm, I went on the solar-powered Amtrak/e-bike adventure that was the genesis of this blog. And it worked! It felt amazing to be out in the world, connecting with people, thinking hard about energy and how we might get what we need without fossil fuels, and writing about it. Then the trip was over, and I went back to my research, and I became pretty unhappy again. I felt there was a clear pattern: I felt good and excited when I was actively engaged with all things solar, whereas working on my cloud research made me depressed and anxious.

So I started to run away from clouds whenever I got the chance. If you’ve been following the blog, you basically know the rest of the story, right up to the moment when I drove my electric truck to Island Pond to see this eclipse.

So there I was, thinking about all this, when suddenly I realized something.

Everyone at Island Pond was running from the clouds, too. We were all there for the sun.

This made me want to cry, but I didn’t want to worry the happy families surrounding me on the beach, so I packed up my stuff and walked through a lumber yard to find a more private spot on the lakeshore. There, I took in the rest of the pre-eclipse and the first half of the partial eclipse, letting the waves of emotion wash over me in a cathartic release. As totality approached, though, I realized I was ready to be back with my people. I returned to the beach, which was way more packed than when I had left it, and settled in for the show.

It turns out the difference between totality and a 99% partial eclipse is literally night and day. When the world went dark and people started whooping, I removed my eclipse glasses and looked up into the Eye of Sauron. It stared back at me. I experienced an auditory hallucination of a roaring, yawning drone.

And, with perfect comedic timing, a manmade cloud — a plane contrail — drifted in front of the sun just at the moment of totality. I had to laugh.

—Jake